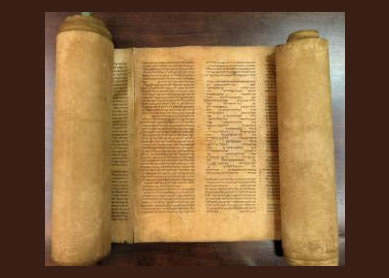

Combining laws and narratives, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) contain a legendary account of the origins of Israel that stretches from the creation of the world to the death of Moses. While late antique Jewish and Christian authors believed that Moses authored this collection, Genesis–Deuteronomy is the result of a long compositional and editorial process, stretching over several centuries, from the Neo-Assyrian (ca. 912–612 BCE) to the Persian period (ca. 538–323 BCE). Because it comprises five books, or scrolls, the collection came to be known as the “Pentateuch” in antiquity. However, the main term used to denote this collection in ancient Israel was the “Torah,” a term meaning “instruction, teaching.” Unraveling the process by which the Pentateuch became the Torah, that is, the instruction par excellence, is also a way to discover how this collection became the most authoritative document in ancient Judaism.

Why are Genesis–Deuteronomy called Torah?

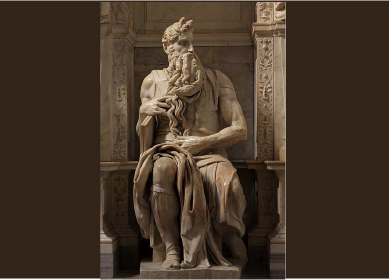

“Torah” is a Hebrew term deriving from the verb y-r-h, meaning “to teach, instruct.” It is generally used to denote instructions of divine origin, which can be associated in the Hebrew Bible with priests, prophets, sages, as well as other authorities. Initially, it appears to have been applied to the set of divine instructions revealed to Moses at Mount Sinai/Horeb and transmitted to Israel through his authority. We consistently observe this usage of torah in Deuteronomy, as well as other texts, such as Mal 4:4, which contains the following admonition: “Remember the torah of my servant Moses, the statutes and ordinances which I commanded him at Horeb for all Israel” (NRSV). Gradually, the “torah of Moses” came to denote the entirety of the traditions associated with Moses. Several compositions from the Persian and early Hellenistic periods (ca. late sixth to the early third century BCE), such as Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles, use the expression “torah of Moses” to refer to a collection that broadly corresponds to Genesis–Deuteronomy. In some passages, like Neh 8:1, this collection is also designated “the book [seper] of the torah of Moses,” an expression that may have been used initially for Deuteronomy specifically (see Josh 23:6; 2Kgs 14:6) and later extended to include Genesis–Numbers.

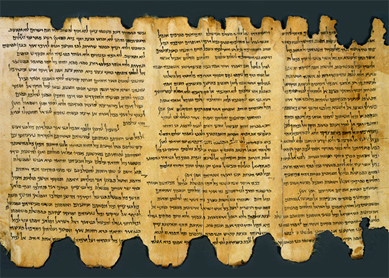

The term torah, however, was never simply identical with the Pentateuch. Rather, it continued to be used as a general term for divine instructions, as can be seen, for example, in the late Ps 119. In addition, the expression “torah of Moses” in the Second Temple period (ca. 515 BCE–70 CE) was not restricted to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. It could also include additional revelations associated with the figure of Moses. The book of Jubilees, a second century BCE composition, expressly claims the authority of Moses and was regarded by the Qumran community (and even beyond) as part of Moses’s torah. In other words, in the Second Temple period the collection of Genesis to Deuteronomy became the torah par excellence, but it was not the only torah.

How did the Pentateuch become so important for Jews and Samaritans?

The elevation of the Pentateuch to the status of Torah was a long and complex process, which can no longer be reconstructed in detail. It probably began in the Neo-Assyrian era, when the first traditions about Moses began circulating, and continued throughout the Second Temple period. The fact that the books of Genesis–Deuteronomy were translated into Greek in the third century BCE suggests that their special status was already recognized by the end of the Persian period. With time, the populations of Judea and Samaria, as well as the various communities of the diaspora, came to recognize the authority of these books and consequently came to adapt their customs to their contents. Such a process was presumably encouraged by the texts that claim a special form of authority for the Pentateuch. Observe how Deut 34:10-12 highlights the unique status of Moses as prophet and lawgiver, asserting that “never again did there arise in Israel a prophet like Moses” (v. 10).

One recent theory about how the Pentateuch acquired special authority emphasizes the collaboration between Jewish and Samaritan communities in the Persian period. Both of these communities worshiped the divinity Yahweh at their respective sanctuaries at Jerusalem and Mount Gerizim and had a shared interest in creating and promoting an authoritative document establishing key customs. In effect, the Pentateuch contains all the main features through which an ethnic group in antiquity could define and maintain its identity: a shared deity (Yahweh), a shared sanctuary (the tabernacle), shared rituals and customs, as well as a shared narrative of origins. This might explain why the same Pentateuch (more or less) was accepted as Torah by Jewish and Samaritan communities settled in diverse locations, both inside and outside the land.