Q. How many gospels were “excluded” from the Bibles as we know them today? And why?

A. Thanks for a great question! It’s a little tricky to answer. First of all, we don’t know how many gospels were excluded, because we don’t know how many gospels once circulated. Maybe hundreds! If you look at the table of contents of Wilhelm Schneemelcher’s %%New Testament Apocrypha (a standard scholarly reference), it details 35 writings with “Gospel” in the title, some of which you may know, including the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Mary. But Schneemelcher’s book only includes surviving gospels or the ones whose titles are at least known.

Also tricky: what constitutes a “gospel”? It’s a perplexing genre. While we recognize the four canonical gospels as all being similar, there are differences between them. For example, they are all biographies of Jesus, whereas by contrast, not one of our surviving noncanonical gospels is. The Gospel of Thomas is a sayings collection with no narrative. The Gospel of Mary is primarily a description of the cosmos, with Mary speaking to the other disciples after Jesus’s death.

There’s also the issue of labels. The Gospel of Mark calls itself a gospel in

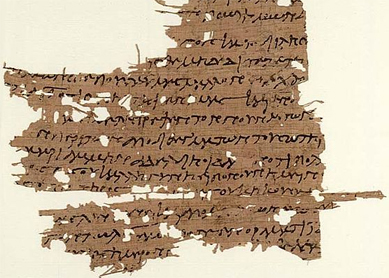

Then there is the curious case of the Egerton Gospel, which looks a lot like a canonical gospel, but which preserves some unique Jesus-sayings; unfortunately, we don’t have very much of it, so we are not sure how it related to the canonical gospels, nor how widely it circulated, nor what it was called, nor even when it dates from. What it does tell us is that there were other ancient biographical gospels that fell out of use.

I note your use of quotation marks around the word “excluded.” You know, then, that we can’t really talk about gospels being deliberately excluded from the canon when it was compiled, probably in the fourth century. The process of canon development is complex and opaque, but by the time the New Testament was compiled, probably most other gospels were no longer known or widely circulated.

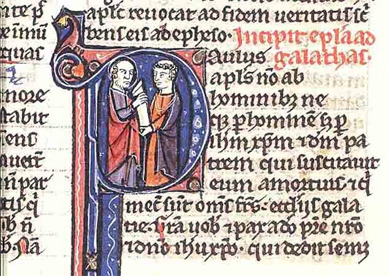

The most famous and most early discussion of the topic is from Irenaeus of Lyon, who argues forcefully around 180 C.E. that there could only be four gospels, just as there are four winds and “four zones of the earth” (Adversus Haereses 3.11.8). This tells us, first, that in Irenaeus’ time there were more than four gospels circulating (although other communities Irenaeus complains about elsewhere used only a single gospel, so his insistence doesn’t mean “only four” as much as it could also mean “more than one”!); second, if we want to talk about “exclusion” from an established canon, the canonical four were already authoritative by the second century, although it would take another 150 years before Bibles similar to ours were produced and circulated.