Passover is an important biblical festival, originating in the agricultural calendar. The ancient Israelites were farmers whose festivals were determined by the cycles of the agricultural year. Springtime was the time when young herd animals, usually born in early winter, were ready for slaughter. This occasioned a family celebration in the form of a sacrificial meal. Springtime was also when the first grains appeared, signifying new life and thus becoming an occasion for celebration. These two agricultural festivals became historicized in the Bible: the sacrificial animal was linked to the tenth plague, when animal blood was smeared on Israelite doorposts so that God would protect those homes; and grain appears as the unleavened bread (matsah), that did not have time to rise because of the hasty departure from Egypt.

What are the biblical sources for the Passover?

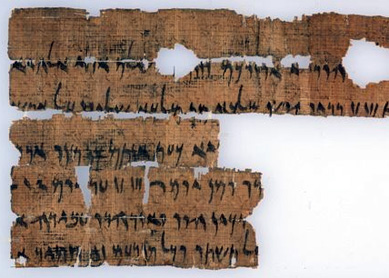

Most biblical references mentioning the Passover or Feast of Unleavened Bread appear in legal materials of the Pentateuch, and the details differ. Exod 23:14-15 and Exod 34:18 mention the seven-day Feast of Unleavened Bread but not Passover at all. Deut 16 mentions the Passover sacrifice together with eating unleavened bread for seven days, but its list of festivals (Deut 16:15) mentions Unleavened Bread but not the Passover. Lev 23:5-8 and Num 28:16-25 ordain a Passover offering on the fourteenth day of the first month, followed by seven days in which unleavened bread is eaten; these are two separate but contiguous holidays (cf. Ezek 45:19), but this passage is much shorter than the one ordaining Tabernacles (Booths), suggesting that Tabernacles was more important in the late biblical period.

The most prominent narrative introducing both the Passover and unleavened-bread feasts appears in Exod 12:1-13:10 in the passage about God slaying the Egyptian firstborns. On the fourteenth day of the first month a lamb is to be slaughtered, with its blood smeared on the doorjambs and lintels of Israelite houses. The lamb is then “roasted over fire with unleavened bread and bitter herbs” (Exod 12:8). This sacrificial animal, called the “Passover,” signifies that God will “pass over” (Exod 12:13) the marked Israelite dwellings and spare their firstborns. This provides a popular etymology for pesakh, the Hebrew word for Passover, but pesakh more likely means “protect”; the animal offering is thus a “protective offering.” The sacrificial offering initiates a seven-day feast featuring bread that was not leavened because of the hasty Israelite departure from Egypt (Exod 12:39).

Consecutive celebrations of the Passover sacrifice and the Feast of Unleavened Bread appear in a passage about the Israelite entry into the promised land (Josh 5:10-11) and in the accounts of Hezekiah (2Chr 30) and Josiah (2Kgs 23:21-23; 2Chr 35) keeping these feasts. Ezra 6:22 mentions the unleavened-bread festival but not the Passover.

The Passover plays an important role in the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 14:12; Matt 26:17; Luke 22:7; cf. 1Cor 5:7), where it is intertwined with the unleavened-bread feast. However, because the ritual “order” (seder) for the Passover meal was probably not set until the second century CE, the Last Supper was unlikely a Seder.

What is the meaning of the Passover celebration?

The narrative in Exod 12:1-13:10 (see also Deut 16:1-3) provides the most explicit information about the meaning of the festivals of Passover and Unleavened Bread, whether sequential or combined. This text historicizes the two agricultural festivals, thus connecting them to the concept of freedom as expressed in the exodus story.

In tying recollection of the past with ritual activities, the Israelites became a people of memory. The concept of memory appears in the Exodus narrative (“day of remembrance” in Exod 12:14 and “remember this day” in Exod 13:3). But the festivals were more than commemorative; they become experiential. Eating sacrificial meat and unleavened bread transports celebrants into a reenactment of what happened in the past, so that they too “experience” the profound transition from servitude to freedom. Performing the rituals of the Passover and unleavened-bread feasts has the effect of making all who observe these festivals, from biblical times to the present, profoundly aware of the central meaning of the exodus story: liberation from servitude by a salvific god. The values and experiences represented by the ritual elements of these festivals––sacrificial animal representing the blood on Israelite doorposts in Egypt; unleavened bread representing the hasty departure––thus contributed to the formation of a national Israelite identity. Indeed, the rationale for many biblical precepts (e.g., the Sabbath commandment, Deut 5:15) is the memory of the deliverance from bondage, which is kept fresh by the springtime festivals.

After the destruction of the temple (70 CE), when animal sacrifice came to an end, the Passover and unleavened-bread festivals were inextricably connected in one holiday, Passover. The paschal sacrifice became signified by a roasted bone, as specified in the second-century CE rabbinic list (m. Pesah. 10) of Passover ritual items, most of which do not appear in the Bible.

Bibliography

- Bokser, Baruch. “Unleavened Bread and Passover, Feasts of.” Pages 755–65 in vol. 6 of The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Edited by David Noel Freedman. New York: Doubleday: 1992.

- Meyers, Carol. Exodus. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Vanderkam, James C. “Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread.” Pages 388–92 in vol. 3 of The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible. Edited by Katherine Doob Sakenfeld. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2008.

- Klawans, Jonathan. “Was Jesus’ Last Supper a Seder?” Bible Review 17 (2001): 23–33, 47.