Jezebel, the prototypical evil queen of the Bible, has often been used as a racist stereotype against African American women.

Who is Jezebel?

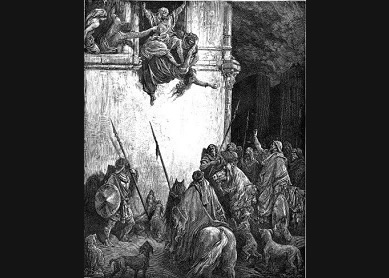

The biblical Jezebel was from Sidon, in present-day Lebanon, and worshiped Baal (1Kgs 16:31). Her husband King Ahab of Israel followed her lead, earning both of them the wrath of the prophet Elijah. Jezebel threatened to kill Elijah, who then ran for his life (

What do these stories have to do with black women?

In

However, the sexualized image her name invokes has been used against African American women since at least the eighteenth century. White slaveowners regularly justified their sexual abuse of enslaved women by insisting that black women were jezebels, that is, naturally more promiscuous and tempting than white women. This insistence was linked to differences in shape between white women and black women, particularly regarding breasts and buttocks. In the nineteenth century, Sara Baartman, a black woman from South Africa, was regularly displayed throughout Europe as proof of black women’s animal-like sexuality because of her large buttocks; called “Hottentot Venus” as a way to highlight her race and her body, her sexual organs remained on display in a Paris museum until the 1970s.

After emancipation, black women were still presumed to be sexually available to white men because of their innate inability to control their sexuality. Even young girls were subject to this stereotype, as postcards from the United States in the early twentieth century show young black girls with prominent buttocks, short skirts, and exposed shoulders. One has a girl sucking on a banana in imitation of a sex act. The postcards do not use the term Jezebel, instead showing stereotypical images of black girls’ promiscuity.

Precisely because black women were often denied the luxury of being treated as “ladies,” a title reserved for white women, the Jezebel stereotype reinforced what is now called the politics of respectability in African-American communities. Jezebel’s “idolatry,” or worship of her native deity, made her a dangerous woman, worthy of being killed. Black women, on the other hand, were seen as unworthy of respect in society because of their natural skin color, so they had to look and act their absolute best in public in the hopes of avoiding humiliation, assault, or worse. This led to community policing of a girl’s clothing, hair, speech, mannerisms, and sexual activity. Today, movements such as the natural hair movement and sex positivity are ways for African-American women to resist the Jezebel stereotype that has labeled them as whores. However, the term itself has not died, resurfacing as late as 2021, with some white Southern Baptist ministers calling Vice President Kamala Harris a “Jezebel.” The Jezebel stereotype remains a reminder of the ways a dominant culture can use a biblical image as a justification for racism and sexism.

Bibliography

- Copeland, M. Shawn. Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2009.

- Lomax, Tamara. Jezebel Unhinged: Loosing the Black Female Body in Religion and Culture. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Patton, Stacey. Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America. Boston: Beacon Press, 2017. (particularly chapter 8, which has images of the postcards described in https://www.bibleodyssey.org/passages/related-articles/Jezebel-from-an-African-American-Perspective )