The celebration of Christmas has had a bumpy history, and Luke’s nativity story is partly responsible for that. Mark, the earliest of the four canonical Gospels, passed over Jesus’s infancy and youth, introducing him as a grown man. Only then did God first address him as his son. Mark’s account left open the possibility that God had not chosen Jesus as the Messiah until he had begun his public career; before that, Jesus might have been merely human. Writing more than a decade after Mark, Luke (and also Matthew) responded by telling a nativity story, partly in order to show that God had chosen Jesus before he was born.

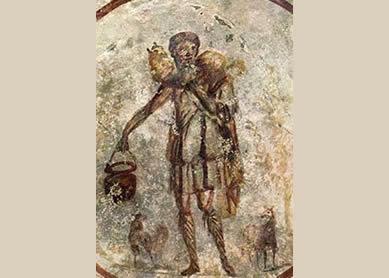

But early Christians did not celebrate the nativity. Not until 395 C.E. did the church officially add that event—Christmas—to the ecclesiastical calendar. They did so in part to address a different theological challenge: the assertion that Jesus had not been a physical being at all but was rather a noncorporeal spirit who merely seemed to take on human form. What better way to demonstrate that Jesus was human than to commemorate his physical birth?

Unfortunately, no evidence remained of when that had taken place. True, Luke memorably tells of shepherds sleeping out in the fields, “keeping watch over their flocks by night” (

By placing the new holiday in late December, the church guaranteed it would become popular, since this was already a season of midwinter revels. For the inhabitants of the Roman Empire, the holiday was called “Saturnalia”—a festival of the winter solstice and a celebration of the bounty of the completed harvest. Saturnalia was a time of role reversals and seasonal license, when everyone took time off from ordinary labor and let off steam.

Christmas never did become a purely religious holiday. Throughout Europe over the centuries, bands of youths roamed from house to house at Christmastime, singing rowdily as they begged for alcohol and money—celebrating, as one critic put it, “by Mad Mirth, by long Eating, by hard Drinking, by lewd Gaming, by rude Reveling.” Ironically, Christmas proved difficult to Christianize.

For more than a thousand years the church mostly turned a blind eye. But the Protestant Reformation changed that. Calvinists in particular waged war on Christmas. Geneva banned its celebration as early as the 1530s. More than a century later, Puritans in both Old and New England did the same. Their reasons were partly theological—Jesus never called for the celebration of his birth, and none of the Gospels indicated the date. But the Puritans had moral reasons too for opposing Christmas. As Boston minister Cotton Mather put it in 1712, “the Feast of Christ’s Nativity is spent in Reveling, Dicing, Carding, Masking, and in all Licentious Liberty.” Mather summed it up by quoting an eminent sixteenth century English bishop: “Men dishonour Christ more in the twelve days of Christmas, than in all the twelve months besides.”

After 1800 Christmas slipped back into New England. And both there and in other regions of the United States and in Europe, it underwent a deep transformation. The profane aspects of the holiday became centered on the family, and especially on the gratification of children. Once again the nativity story played a role in the change. For the great tide of humanity who migrated from farm to city in the 1800s, Luke’s pastoral imagery of shepherds visiting the infant Jesus in a manger would have acquired a new nostalgic tug. More importantly, Luke’s story offered middle-class families a new way of regarding their own children, almost like the infant Jesus, with attention that verged on adoration.

So powerful was this change that during the 1800s Christmas virtually displaced Easter as the most important day in the Christian year. In the process, the holiday assumed its modern form: as a ritual that was both domestic and commercial. Luke’s nativity story was part of this transformation, too.

Bibliography

- Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

- Miles, Clement. Christmas in Ritual and Tradition, Christian and Pagan. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912. Repr., Detroit: Gale Research, 1968.

- Kelly, Joseph F. The Feast of Christmas. Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 2010.