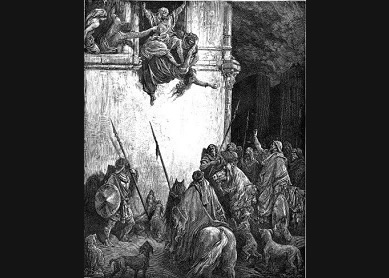

The biblical story of Naboth’s vineyard (

In the book of Deuteronomy, the elders hear accusations prior to a criminal’s execution: the “stubborn and rebellious son” is stoned to death only after his parents appear with him before the elders (

For an accusation to stick, it must not only be made in a proper venue; it must also follow the proper procedure. To this end, Jezebel specifies that there be two witnesses, not just one, to accuse Naboth. This brings the process into line with biblical laws that explicitly prohibit punishment on the basis of just one accuser’s word (

Apart from these procedural matters, the charge itself, had it been true, would have had the legal outcomes that Jezebel and Ahab imagined. Had Naboth actually “cursed God and the king” (

If a man, who has not yet received his inheritance share, speaks treason or flees, the disposition of his inheritance share shall be determined by the king.

Like Ahab, the Assyrian king assumes control of the traitor’s inheritance property, in place of the traitor and any other heirs. By convicting Naboth in a kangaroo court before his execution, Ahab and Jezebel attempt to launder their corruption in the machinery of justice. Their accusation is rooted in law, but so is the punishment God metes out to them. False accusation, according to the Bible and other ancient legal sources, entailed “do to the false witness just as the false witness had meant to do to the other” (

Bibliography

- Magdalene, F. Rachel. “Trying the Crime of Abuse of Royal Authority in the Divine Courtroom and the Incident of Naboth’s Vineyard.” Pages 167–245 in The Divine Courtroom in Comparative Perspective. Edited by Ari Mermelstein and Shalom E. Holtz. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

- Westbrook, Raymond, ed. A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

- Roth, Martha T. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995.

- Sarna, Nahum. Studies in Biblical Interpretation. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2000.