Universalism in the prophets does not refer to the idea among some Christian theologians that all people will be saved at Judgment Day. Rather, it refers to the idea that the religious message of the prophets is directed to all nations. Some have argued that universalism began with the gospels and Paul. In fact, it begins in the Hebrew Bible.

What universal themes appear in the Hebrew Bible?

In Genesis, the names used for the first human beings—Adam (Human) and Eve (Living)— may show that their real identities have been deliberately submerged so that they can represent all of humanity in its relationship to Yahweh. Of Abraham, it was said that all the nations of the earth shall be blessed in him (Gen 18:18), a vision repeated to Jacob (Gen 27:29, Gen 28:3-4) and the patriarchs Judah and Zebulun (Gen 49:10, Deut 33:19). In 2Sam 22:44, David’s kingship rises to the level of other ancient Near Eastern kings who aspired to world rulership. Similarly, 1Kgs 4:34 records that people came from all the nations to hear the wisdom of Solomon, king of Israel. The God of the Hebrew Bible is also said to rule over all the kingdoms of the nations (e.g., Exod 19:5, Deut 32:8, Jer 10:7), a notion that becomes even more pronounced in the Psalms (see, e.g., Ps 22:27, Ps 46:10, Ps 96:1-13). Such universalism fits well within their ancient Near Eastern context. Since the beginning of civilization, rulers dreamed of creating an empire under which all human beings would unite. This vision was said to receive fulfillment in the temple of Solomon (1Kgs 8:43, 1Kgs 8:60, 2Chr 6:33, 2Chr 7:20). The failure of the monarchy, however, led to the failure of that first vision and the need for its restoration, a task the prophets undertook.

What universal themes appear in the prophets?

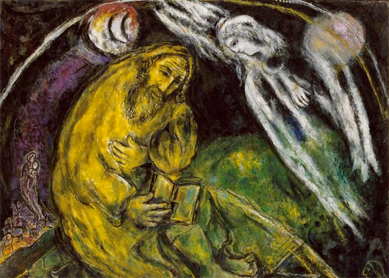

The Hebrew prophets placed the universalism of Yahweh’s rule at the center of their vision for the future. They commonly understood Yahweh to be a universal ruler, not merely a local god who reigned in Jerusalem; they understood prophets to be messengers of Yahweh to the nations; they expected a universal messiah who would bring all the nations to Yahweh; and they lived through historical circumstances that seemed to be fulfillments of this promise, but fell short, and needed to be recast in the future.

Micah envisions nations streaming to Yahweh in Jerusalem. Habakkuk said that “the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the LORD, as the waters cover the sea” (Hab 2:14). Zephaniah sees a day when “all of [the peoples] may call on the name of the LORD and serve him with one accord” (Zeph 3:9). Zechariah spoke of many peoples and strong nations coming to seek the Lord in Jerusalem (Zech 8:22, Zech 12:3).The prophet Isaiah dreamed of the day when all the nations would stream to the house of God (Isa 2:2-4) and finally be delivered from death itself (Isa 25:6-8). In Isa 9 and Isa 11, the prophet dreams of the day when the nations will see a great light, a prophecy that has often been read with messianic expectations (e.g., Luke says the prophecy was fulfilled in the birth of Jesus). Yahweh’s house was to be a house of prayer for all peoples (Isa 56:7). Indeed, Isa 40-66 is filled with universalistic themes. In one of the most universalistic passages in the prophets, Joel sees a day when the Lord will pour out the Spirit on “all flesh” (Joel 2:28-29).

Jeremiah’s title is “prophet to the nations” (Jer 1:5). He was given power, through his prophetic messages, to destroy and build nations, with the end goal that all nations would eventually gather in Jerusalem to worship the Lord (Jer 3:17). Similarly, Isaiah spoke to Cyrus, the world ruler at the time, to say that he, Cyrus, was God’s appointed leader leading to worldwide conversion (Isa 45).

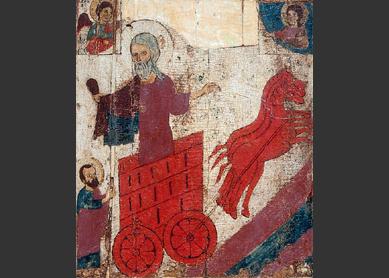

In Zech 9:9-10, the future messiah is promised to bring peace to the nations, a vision echoed in Mic 4. In Isa 42, the Servant of the Lord, a messianic term, is promised as a light to the nations. Both Jeremiah and Ezekiel talk of a “new covenant,” which will supersede the covenant of Moses. The idea seems to be that a new people will be created or re-created from the old, and this is how Yahweh will display his holiness before the nations (see, e.g., Ezek 36:24).

Daniel believed that this vision was fulfilled when King Nebuchadnezzar and Darius the Mede each proclaimed the universal rule of Yahweh (Dan 4; Dan 6:25-27). Yet this was only temporary since they were superseded by other rulers. The Persian king Cyrus was said to fulfill this vision in the rebuilding of the temple at Jerusalem (2Chr 36:22-23, Ezra 1:1-4, Isa 44:28). Yet he too eventually passed, and the temple itself was a disappointment (Ezra 3:12). It appeared that vision might come to fruition in the startling triumph of the Maccabees in the second century BCE, yet that hope also perished under the Roman Empire.

Yet the prophetic vision did not die; it continued in the hope of the rabbis for a new restoration in Jerusalem and the followers of Jesus in his proclamation of a spiritual kingdom for all nations. The Hebrew prophets crafted a compelling vision of an all-nations universal message that continues to persist today.