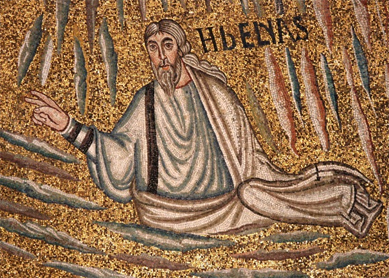

It is hard to imagine a more dramatic biblical figure than the prophet Elijah (1Kgs 17-19, 1Kgs 21, 2Kgs 1-2). He appears abruptly without genealogy or credentials. He speaks and things happen. He is regarded as a healer, miracle maker, king breaker, and, especially, as an ardent opponent of Baal worship. Elijah was active in the first half of the ninth century B.C.E. and is one of the lenses through which we encounter the reign of Israel’s King Ahab and his (in)famous queen, Jezebel. It is noteworthy that while there is agreement on the existence of Elijah as a religious figure, given the composite nature of the Elijah narratives, the legendary and fanciful character of some of the Elijah stories, and Elijah’s paradigmatic portrayal as ‘a prophet like Moses,’ (Deut 18:18), there is very little agreement on the historical reliability of the narratives about him.

What does the ‘sound of sheer silence’ say about social change?

Elijah is portrayed as a kind of lone ranger, a hero who saves Israelite religion by staging a fiery contest on Mount Carmel and proving decisively that Baal does not hold a candle to the biblical deity, Yahweh. In the flush of victory, Elijah slaughters the prophets of Baal, rouses Queen Jezebel’s ire, and flees for his life to Mount Horeb, the mountain of God. There, hidden in a cleft that once sheltered Moses, Elijah complains, rather ironically given the outcome of the contest, that he and he alone of all Israel serves Yahweh zealously. Then, after being buffeted by wind, fire, and earthquake, Elijah hears a soft murmuring sound, the “sound of sheer silence” (often translated as a “still, small voice” of God; (1Kgs 19:12)), that assures him that he is not alone. After all, there are 7,000 Israelites who have not accepted Baal, and there is Obadiah, a prophet who has worked from within King Ahab’s very court to subvert royal policy (1Kgs 18:3-15). That voice demands recognition from Elijah that real political and religious reform requires the blending of one-time displays of power and might with the more frequent acts of passive resistance from the inside, that being an effective prophet requires interaction with people, not isolation from them. Not surprisingly, the voice sends Elijah back into the world to anoint the figures who will change it (1Kgs 19:15-17).

Why isn’t there a mentor handbook for prophets?

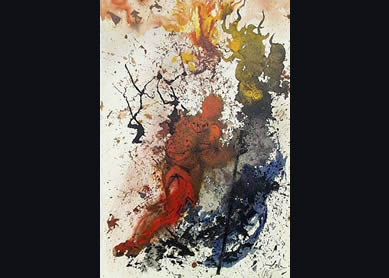

Prophets were active in actual communities, and one of the ways in which their social connectedness was made visible was through mentoring those communities. Indeed, Elijah becomes the quintessential mentor whose task it is to reconcile parents and children (Mal 4:5-6). But Elijah certainly did not start out that way. He bursts on the scene with no mention of family (1Kgs 17:1), and when he flees from Jezebel’s wrath, he laments that he is no better than his ancestors (1Kgs 19:4). The impression we get is that because Elijah did not have effective mentors to shape him for his prophetic role, he is totally unprepared to mentor Elisha, his successor. In fact, right after he calls Elisha to join him, he pushes Elisha away, saying, “Go back again; for what have I done to you?” (1Kgs 19:20) and “Stay here, for the Lord has sent me [on]” (2Kgs 2:2). Yet Elisha, a man with strong family ties (“Let me kiss my father and my mother, and then I will follow you,” 1Kgs 19:20), refuses to leave (2Kgs 2:2). His insistence on staying with Elijah stems from his recognition that the best way to learn what his new job entails is by shadowing a master at work. And eventually, Elijah picks up on that. As their time together draws to a close, Elijah asks what he can do for Elisha. The younger man responds, “Please let me inherit a double share of your spirit” (2Kgs 2:9). Of course, he has “asked a hard thing” (2Kgs 2:10), but then Elisha does have a very hard road in front of him. Elijah agrees to Elisha’s request, provided that Elisha witnesses his departure in a whirlwind (2Kgs 2:10-11).

Since there was no definitive line of prophetic succession in this early period of Israel’s history, it is not surprising that there was no mentor handbook that one prophet passed on to the next. What there was, however, was time together, an apprenticeship period, perhaps, as was common in other professions at the time. It may be that this apprenticeship took place within the small prophetic communities known as “sons of the prophets.” There, mentor and protégé could share successes and failures, important information could be imparted and passed on, and the spirit that those in power sought to silence could be nurtured and fanned into flame.

Bibliography

- Rowley, H. H. “Elijah on Mount Carmel.” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 43 (1960), 190–219.

- Lindbeck, Kristen H. Elijah and the Rabbis: Story and Theology. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

- Moore, Rickie D. “The Prophet as Mentor: A Crucial Facet of the Biblical Presentations of Moses, Elijah, and Isaiah.” Journal of Pentecostal Theology, Volume 15 (2007): 155–72.

- Brueggemann, Walter. Testimony to Otherwise: The Witness of Elijah and Elisha. St. Louis, Mo.: Chalice Press, 2001.