Jews and Christians in antiquity were fascinated by Enoch, an obscure figure from a genealogy (a list of ancestors) in Gen 5. We know this because people left behind many religious texts that mention this patriarch, who is said to live in the seventh generation following Adam and Eve. What interested people in this man who lived prior to the flood and was the great-grandfather of Noah? In writings including the books we know today as 1 Enoch and 2 Enoch, Enoch is a wise man and a scribe who shares visions of extraordinary journeys and secrets of the cosmos. Like a prophet, Enoch delivers stern messages and judgments from the divine, though he also intercedes for fallen angels and consoles the righteous. Many of the texts associated with Enoch are also apocalyptic and anticipate God’s acting definitively to right wrongs and transform the world as we know it.

How is Enoch portrayed in the Bible and other early Jewish and Christian writings?

In contrast to these vivid descriptions, the Bible’s presentation of Enoch is rather limited. Enoch’s appearances in biblical texts relate especially to his role in the genealogy or among famous ancestors (Gen 5:18-19, Gen 5:21-24; 1Chr 1:3; Sir 44:16; Sir 49:14; Luke 3:37; Heb 11:5). There is, however, a remarkable description of Enoch among the list of ancestors in Gen 5. Unlike the other patriarchs, who die after extremely long lives, Enoch is said to have “walked with God” and to have been taken by God (Gen 5:24). This cryptic statement may have inspired the abundant literature about Enoch that flourished in early Judaism and Christianity. Or, it may reflect a rich tradition about the patriarch that already existed and at which biblical texts only hint.

Many scholars understand the vibrant traditions about Enoch emerging from close reading and interpretation of Genesis. From their perspective, early Jews and Christians intensely studied a book like Genesis and sought to explain further aspects of the text that were not clear or obvious for their communities. Enoch’s distinctive presentation in Gen 5’s brief genealogy invites speculation. A reader of Gen 5:21-24 might ask, “Why did God take Enoch?” “Where did Enoch go when God took him or what did he do?” Enoch’s enigmatic departure from earth may have led later interpreters of Genesis to imagine that, once taken, Enoch spent time with God or angels and received divinely revealed knowledge. Ancient Jewish literature, like the book of Jubilees, with expansions or clarifications of traditions familiar from the Bible, may provide such a context for the development of stories related to Enoch.

At the same time, Enoch’s being taken by God is similar to ancient Near Eastern stories in which a sage like Adapa or Utuabzu or kingly Enmeduranki ascends to the heavens and receives privileged information. Likewise, Enoch’s rebuke of angels who shared knowledge forbidden to humans and had sexual relations with women recalls Mediterranean traditions of boundary-crossing culture bringers like Prometheus and Greek tales of gods mating with mortals. Simply put, traditions associated with Enoch may have been widespread, with ancient roots extending beyond Genesis. This would be rather unremarkable since aspects of Gen 1 and Gen 6-9 resemble elements of Near Eastern accounts like the Enuma Elish and the Epic of Gilgamesh. Thus, some scholars would suggest that both biblical passages and other Jewish and Christian writings about Enoch preserve vestiges of traditions that originated outside of Bible.

Where did the books of Enoch come from and how were they used?

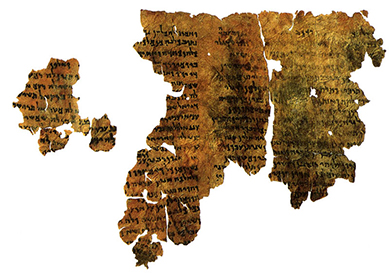

The origin of this exceptional figure remains unclear. The books associated with Enoch do not provide historical information about an actual person from a time of a great flood. Rather, writings like the Epistle of Enoch are considered pseudepigraphal. This means that even though the texts appear to contain the words, visions, or experiences of Enoch, they were, in fact, written by someone else and attributed to the patriarch. There are many other texts regarded as pseudepigraphal that are related to figures from the Hebrew scriptures, such as Levi, Isaiah, or Ezra. While both biblical and nonbiblical traditions set Enoch prior to the great flood, many of the books associated with this patriarch come from the third century BCE to the first century CE The authors of Enochic books may have understood the patriarch’s setting just prior to the great flood (a time of judgment on the world) as similar in some ways to their own context—a connection they wished their readers to make as well.

Books associated with Enoch were popular among ancient Christians, and a selection from the Book of the Watchers (which we find today in 1 Enoch) is quoted in Jude 14-15. Many scholars also think that 2Pet 2:4 and Jude 6 allude to the punishment of fallen angels described in literature connected to Enoch. While interest in books attributed to Enoch eventually waned among Jews and Christians, one can still find references to this mysterious figure in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic literature into the Middle Ages.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Philip S. “From Son of Adam to Second God: Transformations of the Biblical Enoch.” Pages 87–122 in Biblical Figures Outside the Bible. Edited by M. E. Stone and T.A. Bergren. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1998.

- Reeves, John C., and Annette Y. Reed. Enoch from Antiquity to the Middle Ages: Sources from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- VanderKam, James C. Enoch: A Man for All Generations. Studies on Personalities of the Old Testament. Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1995.