When we look at the New Testament, we find that there is no one view of what it means to “be a man.” Instead, the New Testament depicts various models of masculinity or various “masculinities.”

What masculinities do we find in the New Testament?

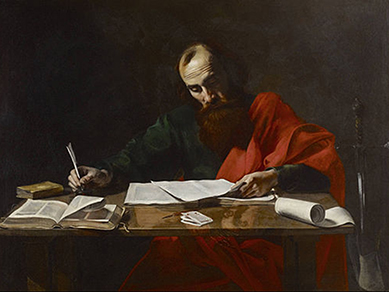

In some parts of the New Testament, masculinity is constructed according to elite standards that were prevalent at the time. Paul’s disputed letters—or letters that lack a scholarly consensus as to whether Paul actually wrote them or not—exemplify this type of masculinity in particular. Ephesians and Colossians, for instance, reflect hierarchal family structures that were typical among the elite when they provide instructions to members of the traditional household (

This portrayal of masculine propriety, however, conflicts with portrayals that we find elsewhere in the New Testament. For one, Paul’s undisputed letters—or the letters that scholars agree were written by Paul—do not promote the traditional household. In 1 Corinthians, Paul prefers that Christians follow his example and remain unmarried (

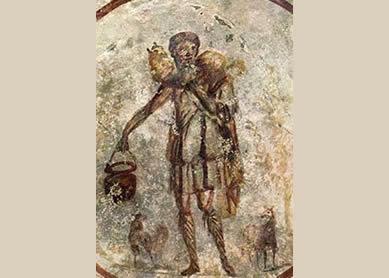

The four canonical gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) also present a different picture of masculinity, especially in how they depict Jesus. Like Paul, Jesus is an unmarried man. He leaves his hometown around the age of thirty (

Within the gospels, though, Jesus’s own masculinity varies depending on which gospel we read. The Gospels of Mark and John, for example, depict Jesus’s death in very different terms. Mark dwells more on Jesus’s bodily violation and lack of self-control, to the point where Jesus cries out in despair from the cross, saying, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (

Yet to complicate matters even more, the same New Testament text can portray Jesus’s masculinity in different—and even conflicting—ways. The Gospel of John, for instance, presents Jesus more in accordance with elite standards, but this Jesus is also flogged, forced to wear a crown of thorns, and pierced in the side with a spear (