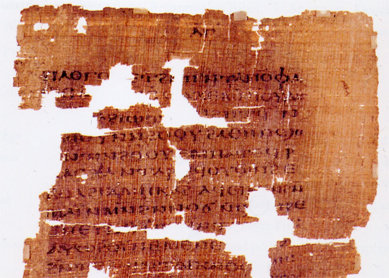

A fourth-century Coptic translation of the Gospel of Judas, which is a second-century gospel first mentioned by Irenaeus of Lyons, was recovered in 2006 and published initially under the auspices of the National Geographic Society as a gospel that exonerated Judas and saw him as a Gnostic hero and soul mate of Jesus. Subsequent studies, however, questioned this interpretation of the Gospel of Judas and resulted in the major revision of the original editors’ thesis and translation. The gospel’s author was affiliated with Sethian Gnostic teachings where the creator-god of the Old Testament (YHWH) was understood to be an archon, a demonic trickster god. He is the main adversary of a higher, transcendent God known only to Jesus and the Gnostic elect who traced themselves back to their hero, Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve.

In the Gospel of Judas, Judas turns out to be demonic in a way that exceeds the New Testament stories about him. First, Jesus calls Judas the “Thirteenth Demon” (in Greek, daimon; 44:21), which in Sethian Gnostic literature is a title given to the chief archon who created and rules the world: Ialdabaoth, a title for God in the Hebrew Bible. This archon is opposed to the transcendent God that the Gnostics worshiped. He tries to lead people astray and keep knowledge of the transcendent God from them. Gnostics believed this evil archon lived in the thirteenth realm, at the top of the universe above the five abysses of chaos and the seven planetary realms. Judas, then, is identified with the chief demon in the Sethian tradition as Ialdabaoth’s double on earth.

Second, in the Gospel of Judas, Jesus tells Judas that the disciples, including Judas, are not part of the Holy Generation. They will not ascend to the transcendent realms as Gnostic elect. Instead, the disciples are ignorant priests who worship Ialdabaoth rather than the transcendent God. Unknowingly, they are leading myriads of Christians astray with their erroneous teachings about Jesus’ sacrificial death and rituals like the Eucharist, or communion, which are nothing more than tricks Ialdabaoth has put into place so that he alone is worshiped (36:11-40:26, 44:15-45:13-19, 46:5-47.1). For Sethians, the transcendent God does not require bloody sacrifices or rituals that reenact them.

Third, Jesus teaches Judas everything there is to know about Judas’s imminent involvement in Jesus’ arrest and death, before the action happens. So Judas has foreknowledge of what he is going to do, which makes his actions conscious, if not deliberate. Fourth, Jesus informs Judas that there is nothing Judas can do about this. It is his fate, however horrible this may seem (46:5-47:1). Upon hearing this, Judas becomes full of wrath and consequently goes on to betray Jesus to the priests and brings about Jesus’ sacrificial death to the chief archon (56:11-58:26).

Certainly this story is unfamiliar to us because it is told from the perspective of the Sethian Gnostics, who did not like the conventional Christian story. This gospel mocks the early apostolic Christian story and its doctrines by pointing out its inconsistencies. If Jesus’ death really is a redemptive sacrifice that atones for sins, why is it that Judas is the one who made this possible? Isn’t Judas the same person whom the early apostolic Christians cursed and the New Testament says was a devil and Satan? Indeed, these Gnostics reasoned, Judas was working as a demon, and this demon was the god of the Old Testament. As long as Christians did not realize this—as long as they continued to be led astray by the teachings of the twelve apostles who were the cornerstone of the early apostolic churches—they would remain servants of Ialdabaoth and never return home to the transcendent God.

Bibliography

- Kasser, Rodolphe, Marvin Meyer, and Gregor Wurst. The Gospel of Judas. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2006.

- Jennot, Lance. The Gospel of Judas. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011.

- Ehrman, Bart D. The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Pagels, Elaine, and Karen King. Reading Judas: The Gospel of Judas and the Shaping of Christianity. New York: Viking, 2007.

- DeConick, April D. The Thirteenth Apostle: What the Gospel of Judas Really Says. Rev. ed. New York: Continuum, 2009.