The Madonna has a thousand faces, even though no one knows what Mary of Nazareth looked like. The obscure peasant woman has inspired more artists than can be named. By some estimates, she is more influential than Jesus in western art.

A long tradition credits Luke with first painting Mary’s likeness—with the assistance of an angel. Luke’s Gospel tells Mary’s story in greatest detail (

Many scenes of the Madonna were inspired by specific biblical texts about Mary. Luke tells us that the angel Gabriel announced that God favored her (

The biblical stories of Mary’s life also provide inspiration for artists to explore dimensions of human spiritual experience. Rembrandt’s Visitation shows Mary and Elizabeth bathed in light (

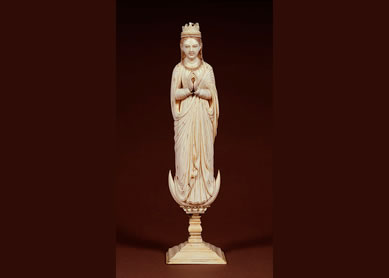

As early as the second century, extrabiblical traditions circulate which imagine Mary’s parents and a childhood that prepares her to be the mother of God (Greek, theotokos); artists use these traditions as well. Dürer painted the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, who comforts her daughter. Mary’s death and immediate welcome (assumption) into heaven, a motif from the eleventh century, present her as queen and heavenly bride. Charonton’s Coronation of the Virgin shows Mary receiving her crown at the heart of God; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (as dove) are all present. These paintings imagine the Madonna able to console and intercede with power and wisdom.

Places of pilgrimage are associated with visions of Our Lady from which come new depictions of the Madonna. Examples are found at Le Pu en Velay, France (the black Madonna, as early as the thirteenth century); Guadalupe, Mexico (sixteenth century); and Lourdes, France (nineteenth century). The Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth, a pilgrimage destination since about the fourth century, although the present shrine was constructed in the twentieth, honors the Madonna with a variety of mosaics from all over the world. The mosaic from Cameroon inside the church depicts the spirit of the Madonna: she hovers over her child and they open their arms in welcome to the women who are carrying baskets full of the substance of their lives.

The art of the Madonna absorbs and presents feminine ideals and religious traditions from all contexts. The resulting motifs take on a life of their own: each image of Mary—virgin, mother, and queen—representing a particular vision of human life.

Bibliography

- Dupré, Judith. Full of Grace: Encountering Mary in Faith, Art, and Life. New York: Random House, 2010.

- Verdon, Timothy. Mary in Western Art. Captions by Filippo Rossi. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2005.

- Ebertshauser, C. M., H. Haag, J. H. Kirchberger, and D. Solle. Mary: Art, Culture, and Religion through the Ages. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1998.