Rome captured the imaginations of ancient Christians for reasons both good and bad. If you’ve read the New Testament, you’ll recognize Rome as the city where Paul received a warm reception from a group of Christ-followers, but also as the location where he and Peter were put to death, according to early Christian tradition. You may also remember the striking image of the whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation—riding on a beast with seven humps—as a symbolic reference to Rome’s famous seven hills (Rev 17:9). To John of Patmos, the author of Revelation, Rome was literally the seat of all evil. To other Christians, however, Rome was home.

Who were Rome’s Christians?

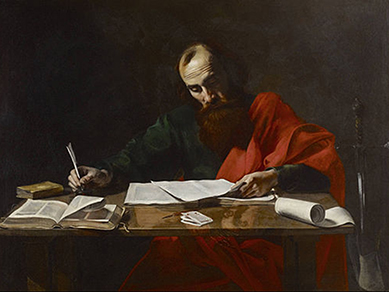

By the time that the apostle Paul visited the city, around the year 50 C.E., there was already a community of Christians there, a small fraction of Rome’s almost one million inhabitants. Paul mentions a number of Roman Christians by name—a group that includes many women (Rom 16). Overall, Paul’s Letter to the Romans provides us with important clues to the nature of early Christian communities in the city. They were likely made up of merchants, tradespeople, and slaves. Many may have been immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean since they spoke—and occasionally wrote—in Greek rather than Latin. Because they owned property and subsidized Paul, they appear to have had money, but they did not belong to the upper classes.

Steadily, Christian communities grew over the second and third centuries, attracting in particular slaves and women of various social classes. Within these communities, disenfranchised members of Roman society found others to care for them when they were widowed or sick and, later, to bury them. They might become leaders or respected people within the confines of house churches. Girls—who were required by Roman law to marry early and produce children—found relief from arranged marriages and dangerous childbirths within Christian groups that considered virgins a special, privileged class. Indeed, for many, the benefits of becoming a Christian outweighed the risks: possible ostracism by one’s family and, only very occasionally, execution as “atheists” (those who did not recognize the gods of Rome).

How might Christians such as those hosting Paul have fared in first-century Rome?

Contrary to popular thinking today, Roman citizens were free to practice the religion of their choice, so long as they satisfied two conditions: There could be no large assemblies meeting covertly, as Roman officials feared resistance movements that could disrupt public order. And citizens had to proclaim publicly their allegiance to the emperor. If they kept their heads down, Christians could get along just fine without fear of persecution. Those unwilling to play by Rome’s rules, however, could find themselves in big trouble. The emperor’s rule challenged Jewish, and later, Christian, commitment to absolute monotheism, since the rise of the imperial cult required that people of the Roman Empire honor the emperor as a god.

Most emperors were prepared to allow their citizens to live peacefully without demanding direct obeisance. But there were exceptions. The emperor Nero (54-68 C.E.) was rumored to have rounded up a small group of Christians following the Great Fire of 64 C.E. Rumors spread that Nero made scapegoats of the Christians, using them as human torches outside his palace. Whether or not this actually happened, Christians and Jews certainly feared and loathed Nero—in fact, the great beast bearing the number 666 featured in Rev 13:18 is, most scholars think, a hidden reference to Nero, since the numerical value of Nero’s name in Greek transliterated into Hebrew adds up to 666.

Both apostles Peter and Paul were executed in Rome under Nero’s reign. The places of their remains became shrines (and in the fourth century, basilicas) where Christian faithful gathered to honor the apostles—at St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, south of the city, and St. Peter’s, on the Vatican Hill. There appears to have been no reason for these visitors to hide their devotion to Christ.

When the emperor Constantine (reigned 306-337 C.E.) converted to Christianity on October 12, 312 C.E., he paved the way for the eventual Christianization of the empire. It’s not clear how many Christians there were in Rome before and after Constantine’s conversion, but certainly after 312 Constantine worked to transform Rome into a fully Christian city, building for public worship a number of basilicas such as St. John Lateran and Holy Cross in Jerusalem and enlarging older sites of Christian worship such as St. Peter’s. His largesse and vision ensured that Rome remains a vital pilgrimage center for Christians to this day.

Bibliography

- Stambaugh, John E. The Ancient Roman City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1988.

- Shelton, Jo-Ann. As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Wilken, Robert . The Christians As the Romans Saw Them . New Haven,CT: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Carcopino, Jerome . Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire. New Hartford,CT: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Angela, Alberto. A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities Rome: Europa Press, 2009.

- Boatwright, Mary T., Daniel J. Gargola, and Richard J. A. Talbert. The Romans: From Village To Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.