The fate of the kingdom of Judah is a central topic of the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical stories, Judean kings ruled from the time of David, about 1000 B.C.E., until 586 B.C.E., when the Neo-Babylonians destroyed Judah, its capital Jerusalem, and the temple and forcefully resettled most Judeans in Babylon. Though the kingdom of Judah was gone, Judean scribes and priests preserved and developed the most prominent biblical literary and religious traditions during and after the Babylonian exile. When the Persian king Cyrus conquered the Neo-Babylonians in 539 B.C.E., he secured the periphery of his empire by allowing his new subjects to return home. Although some Judeans stayed in Mesopotamia, those who returned rebuilt Jerusalem, the temple, and Judean society.

What was the status of the kingdom of Judah in the ancient world?

The kingdom of Judah has had an enormous legacy, despite its small size and relative unimportance on the ancient Near Eastern political stage. It was Judean scribes who produced most of the contents of the Hebrew Bible. The Bible that we know today is the expression of select Judean theologies rooted in a particular time and place but whose impact is now global.

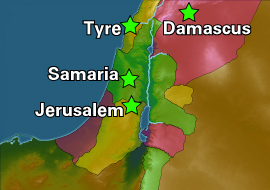

Around 1150 B.C.E., the major civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Anatolia collapsed, leaving a power vacuum in Canaan. The kingdoms of Judah in the south and Israel in the north emerged in this power vacuum, along with Ammon, Moab, Edom, Aram-Damascus, and Philistine and Phoenician city-states, between the 10th and eighth centuries B.C.E. When Egypt, Assyria, and Babylonia recovered, the territory of Judah and its neighbors became a political buffer zone, subject to these empires. This geopolitical context thoroughly shaped biblical stories.

The kingdom of Judah became a vassal to the Neo-Assyrian and, later, Neo-Babylonian kings, meaning that Judean kings had to pay tribute and remain loyal to them. In Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian documents, Judah is not exceptional. In 728 B.C.E., the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III mentions Judah among other subjugated kingdoms that have paid him treasures, goods, and livestock (Summary Inscription 7; see 2Kgs 16). In 701 B.C.E., the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib sacked Judean towns, besieged Jerusalem, and took vast riches from the Judean king Hezekiah (Rassam Cylinder; see 2Kgs 18:13-19:37, Isa 36-37, 2Chr 32:1-23). Although we have no surviving Babylonian accounts of Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of Judah, biblical accounts, including heart-wrenching lamentations over Jerusalem, suggest that he easily quashed Judah’s rebellion (2Kgs 24-25, Ps 79). Despite the biblical depiction of Solomon receiving tribute from neighboring kings and ruling over a kingdom that stretched from the Euphrates in Mesopotamia to the border of Egypt (1Kgs 4:21) the reality was far from that ideal: it was neighboring kings who dominated and subjugated Judah.

How did the status of the kingdom of Judah determine biblical theology?

Many read the Hebrew Bible as a universal, timeless book. However, its authors were primarily concerned with the fate of Judah, especially Jerusalem and the Davidic kings who ruled from there. Judean scribes included statements about the fate of the kingdom of Judah in stories about the 12 tribes attaining the land as well as the establishment of Israel and Judah (for example, Lev 26:39-45; Deut 4:25-31; Josh 23:16; 1Kgs 9:7). They link the kingdom’s stability to Yahweh’s covenants with David and the Israelites: David’s descendants would always rule, Jerusalem would always stand, and the Israelites would possess the promised land. Judean authors reinforced these ideas when they responded to the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 B.C.E.

Historically, the Neo-Assyrians destroyed the northern kingdom for political reasons: Israel withheld tribute whereas Judah did not (2Kgs 17:4-6, 2Kgs 18:9-13). Judean scribes explained Israel’s demise and their own survival by developing theological explanations that affirmed the legitimacy of Judah (2Kgs 17:7-18). They portray Israel’s kings and people negatively, justifying Israel’s fall and framing the political disaster as a lesson for Judean kings and people.

Judean authors faced a crisis of their own in 586 B.C.E., when the Neo-Babylonians decimated Judah. They apologize for this catastrophe by blaming the Judean people, kings, priests, and prophets, accusing them of breaking their covenant with Yahweh. Jer 21:3-6 portrays Yahweh fighting along with the Neo-Babylonian armies, and Ezek 9 describes Yahweh sending divine beings to destroy Jerusalem and kill Judeans! This shocking imagery serves to maintain the idea that Yahweh is in control not only of the Judeans but also of the Neo-Babylonians, whom he has empowered to remove Judah from the promised land. Further responses to Judah’s destruction include a renewed covenant (Jer 31:31, Ezek 36:27, Isa 59:21).

In postexilic, Persian-controlled Judah, Nehemiah (Neh 9:6-37) provides hope by retelling the foundational narrative of Israel and Judah, beginning with creation, through the patriarchs, exodus, and the kingdoms up to the present, postexilic moment. He describes Judeans making a new covenant with Yahweh (Neh 8-10). Granted, this reconstituted Judah did not have a Davidic king, but through the reenvisioning of the foundational narrative and compilation of most of the contents of the Hebrew Bible, these Judean writers, marked by the experience of destruction and exile, sealed the legacy of the kingdom of Judah.

Bibliography

- Grabbe, Lester L. Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? London: T&T Clark, 2007.

- Cline, Eric H. “Did David and Solomon Exist?” The Bible and Interpretation, October 2009.

- Schneider, Tammi J. “Through Assyria’s Eyes: Israel’s Relationship with Judah.” Expedition Magazine 44.3 (Nov. 2002).

- Miller, J. Maxwell and John H. Hayes. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. 2nd ed. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2006.

- Fleming, Daniel E. The Legacy of Israel in Judah’s Bible: History, Politics, and the Reinscribing of Tradition. Cambridge, Engl.: Cambridge University Press, 2012.