According to the Bible, in order to cover up a tawdry affair with Bathsheba, David wrote his commander in chief at the battlefront ordering him to orchestrate the death of her husband (

The epigraphic evidence suggests that certain elements in them are likely fictional. Although writing was practiced in Mesopotamia and Egypt from the third millennium B.C.E., literacy in these cultures was practiced solely by trained scribes. Both cuneiform and hieroglyphics employed hundreds of signs requiring years of study to master. Few people were willing to endure the harsh discipline wielded by teachers of schools for writing.

The emergence of the alphabet in Phoenicia at the end of the second millennium B.C.E. greatly simplified writing. Did literacy become widespread with this new system, which used fewer symbols? The Hebrew alphabet has only 22 characters, but this does not mean that literacy increased—we have ample evidence of societies that have easy writing systems but low literacy rates. So what was to prevent David and Jezebel from becoming literate? For one thing, they lived in an agrarian economy with few incentives for an educated populace. For another, schools in ancient Israel, if any existed, served only the sons of royalty and scribes. Furthermore, the demand for skilled writers was limited and papyrus and parchment were expensive.

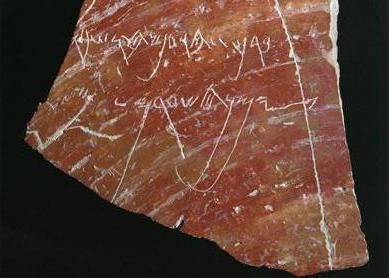

Now, David was a chieftain and Jezebel the daughter of one. Could they have been literate? Possibly, but not likely. And the recipients of their letters were commoners. True, a soldier at Lachish boasted that he read every letter dispatched to him. When was that? Over four hundred years after David—roughly the date of most of the literary evidence that has been excavated from ancient Judean sites. What is the nature of this evidence? Mostly brief notes in ink on potsherds; labels on wine jars; stone seals bearing the owner’s name, often the father’s, and sometimes a title; clay seals for documents; stone weights; an amulet containing a version of

Although most literary remains come from the seventh and sixth centuries B.C.E., not everything is that late. Ostraca from Samaria and the Siloam Inscription date from the eighth century, the latter inscribed on a wall of a tunnel to commemorate a feat of engineering. From neighboring lands came the Mesha Stela (Moab, ninth century), the Gezer agricultural calendar (southern Canaan, 10th century), and plaster tablets about the visions of a prophet named Balaam (Moab/Deir Alla, eighth century).

The crowning achievement of literacy in Israel, the Hebrew Bible, aims to ennoble, not to destroy lives. In it, scribes explore the complex relationship between humans and God. From the second century B.C.E. into the Common Era, the Dead Sea Scrolls and works originating in Alexandria and elsewhere (the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha) continued this endeavor. Still, those who could read and write at this time—mostly men—made up a small percentage of the population.

Bibliography

- Crenshaw, James L. Education in Ancient Israel: Across the Deadening Silence. New York: Doubleday, 1998.

- Van der Toorn, Karel. Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Carr, David M. Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.