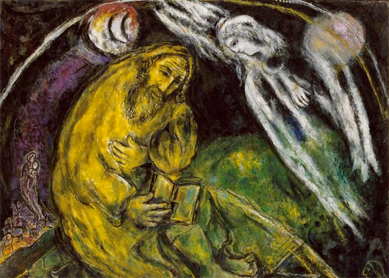

The Jerusalem temple said to have been built by Solomon was destroyed in 587/586 B.C.E., when the Babylonians captured the city, torched it, and exiled the Judean leadership to Babylon. Second Kings describes the final days:

“In the fifth month … Nebuzaradan, the captain of the bodyguard, a servant of the king of Babylon, came to Jerusalem. He burned the house of the Lord, the king’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem; every great house he burned down.” (

This event marked a turning point in Israelite history because it spelled the end of an autonomous or even semiautonomous Judean state. It initiated a period, usually called the exilic period, that came to an end in the biblical record when King Cyrus of Persia conquered the Babylonian empire in 539 B.C.E., subsumed that empire under his own rule, and permitted Judeans to return to the land and rebuild the temple (see

The prophetic books of Haggai and Zechariah portray these prophets as urging the leaders and the people to rebuild the temple.

The Hebrew Bible does not describe the rebuilt temple, although

Whether or not it compared favorably to the first temple, the restored temple marked a new epoch; it signified the renewal of Jewish life after the devastation of exile. Moreover, it signaled a new role for the people themselves. Whereas the first temple was credited to Solomon and was built with forced labor, the second temple was the work of the people themselves. Although it came into being under Persian royal auspices (see

Bibliography

- Williamson, H. G. M. Ezra and Nehemiah. Waco, Tex.: Word Books, 1985.

- Grabbe, Lester L. A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, Vol. 1: The Persian Period (539-331 BCE). London: T&T Clark, 2004.

- Eskenazi, Tamara Cohn. In an Age of Prose: A Literary Approach to Ezra-Nehemiah. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986.